Emotional Granularity and a Good Life

This is unrelated but "Good Life" by OneRepublic is the kind of song that simply could not be made in this decade because it would so fundamentally be misreading the room. The early 2010s were a time.

In the sociological time capsule that is the Tiger King era of the pandemic, another thing that was virally popular was Prof. Laurie Santos’s Coursera class on well-being (here), and honestly, it was great! I did it with my partner and sister and the three of us jointly did the weekly homeworks and had a little well being gang book club that met virtually on Saturdays. The course started off with a free self-survey from the VIA institute (here) which asked a series of questions and then dimensionalized our character strengths and spit out a nice convenient ranked list of, roughly, what helps us thrive. Taken with an excellent guide from Prof. Tayyab Rashid from the University of Toronto (here) on how to more tactically engage in activities aligned with each strength, this exercise was a nice way to shortlist activities that felt like they might liven up our days and weeks.

This was a fun way to pass the time when we were whimsically flirting with being shut-ins, but as the months piled on and social distancing and remote work persisted, we ran into a deep need to reconfigure our lives in a more permanent way. Burnout at work was the norm and, as people looked with increasing desperation for solutions, I found myself coming back often to these documents. Buried in the homework of this class was a profound truth: that we should figure out more granularly what makes us feel alive, that we should find actions that drive these joys and that, well, we should do them.

Let’s start by talking about emotional granularity.

The big idea: Emotional granularity is good for you.

Emotional granularity the practice and ability of better recognizing and articulating how we feel. Neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett in this 2016 NYT article that talks about how people with better “emotional granularity” have a host of better outcomes:

“According to a collection of studies, finely grained, unpleasant feelings allow people to be more agile at regulating their emotions, less likely to drink excessively when stressed and less likely to retaliate aggressively against someone who has hurt them.

Perhaps surprisingly, the benefits of high emotional granularity are not only psychological. People who achieve it are also likely to have longer, healthier lives. They go to the doctor and use medication less frequently, and spend fewer days hospitalized for illness. Cancer patients, for example, have lower levels of harmful inflammation when they more frequently categorize, label and understand their emotions.”

One possible reason is that beyond just the ability to recognize and articulate our experience, emotional granularity allows for better navigation through our life experiences. Writes Barrett:

“With higher emotional granularity, however, your brain may construct a more specific emotion, such as righteous indignation, which entails the possibility of specific actions. You might telephone a friend and rant about the [Flint] water crisis. You might Google “lead poisoning” to learn how to better protect your children. You might call your member of Congress and demand change. You are no longer an overwhelmed spectator but an active participant. You have choices. This flexibility ultimately reduces wear and tear on your body (e.g., unnecessary surges of cortisol).”

In the article Barrett focuses on the benefits of feeling specifically despair vs “a vague sense of badness”, but this practice is, of course, just as important in figuring out the opposite. What does it look like to try to better feel specific joys instead of a vague sense of goodness?

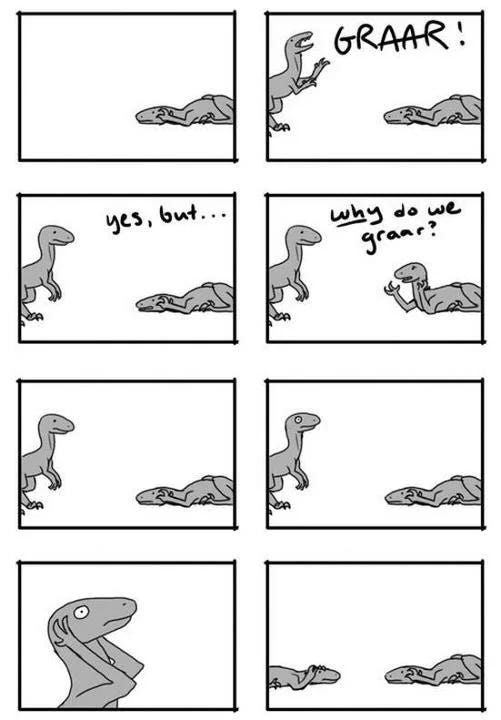

Why do we graar?

One of the bigger lessons I’ve learned over the years is personal growth requires us to better articulate the simple things we haven’t yet examined. A good example is the notion of a life well lived. Growing up in a somewhat classic immigrant family where upward mobility was the clear shared goal, doing well in school was the hamster wheel at our disposal. As I became a more sophisticated rodent, I graduated to bigger and bigger wheels of “school” then “academia” and then “career.” In turn, they all provided structured and measured feedback, and fed my ever growing need for external validation. Fair deal, I guess.

But a persistent and inevitable dread caught up to me in my 20s and brought me to a realization that I…did not know what actually made me happy? That, outside of the sequentially larger hamster wheels, I hadn’t really articulated a sense of what a good life meant for me??

Why did I GRAAR???

Source: ??? I spent like 10 mins trying to figure out where this comic is from and couldn’t - do you know? It’s one of my all time favorites.

I figured understanding how to live a good life could only happen once I better defined what a good life could look like. And so, I went into a few panic stricken internet rabbit holes.

What is a good life?

One thing I found helpful in this pursuit is a great corner of research, initially summarized here by Scott Barry Kaufman in Scientific American that talks about three general sources of goodness. The first two, derived from old Greek notions of hedonia and eudaemonia have been around and discussed for a long time. The third is more novel. A rough overview:

Hedonia:

Happiness driven by the pursuit of pleasure, enjoyment, and the absence of pain or discomfort, centered on immediate gratification and feeling good

Often helped by circumstance (economic, political, personal) that allow for hedonism to flourish, but available in smaller moments when we are mindful, savoring, practicing gratitude, etc.

Think: eating a good meal, getting a massage, binging shows, drugzz

Eudaemonia:

Happiness driven by the pursuit of meaning and purpose in life and lack of existential crises, centered on self-actualization, personal growth, and activities that allow us to find our place in a community and alignment with our values

Often helped by rituals and longer term activities that accrue to something more emergent and meaningful over time

Think: volunteering, regular touch points with friends and family, religious affiliation

Psychological Richness:

Happiness driven by experience of diverse, interesting and life-changing events, absence of regrets and ”what if”s, and centered on a persistent search for novelty through travel, culture, relationships, etc.

Often helped by curiosity, a sense of spontaneity and a willingness or ability to be open to new experiences

Think: living in different places, taking risks, doing things that end up being good stories to tell around a campfire

If you’re interested in a deeper reading, try the paper that introduces the psychologically rich life (here) or, as I prefer, the background section to a follow-up questionnaire study from the same authors (here).

It’s worth noting that based on surveys, when forced to choose one from the above, people tend to prefer them in the order presented above. Depending on the study, roughly about ½ to ⅔ of those surveyed prioritize hedonia, followed by anywhere from ⅙ to ⅓ who prefer eudaemonia, and lagging behind some 1/15 to ⅙ prize psychological richness. This makes intuitive sense and lines up fairly well with established models of human priorities, like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. That said, for many of us the exercise of choosing one over the others isn’t particularly useful. What’s more useful is developing a sense of how our days and activities align with the various ways we find joy and meaning. A critical exercise is to understand if our revealed preferences (that is, the way we actually spend our time) line up with our stated priorities (what we say or think we want).

A wee bit of homework

Knowing the results of the study above, think about how that relates to your own preferences. Do you also prefer hedonia above others? Do you have your fill in life of eudaemonia and psychological richness? Ask yourself: which would you prioritize on a given day if you had to choose one? How would you allocate your time in a month if you had to distribute across all 3? Is how you spend your time now somewhat reflective of the answer you arrive at?

Take the VIA character survey (here and just the free bit!) and see if the character strengths resonate. Consider the list of aligned activities (here) and see if they help tactically fill in any gaps you identify in how you spend your time vs how you say want to.

There is an old Annie Dillard quote that has stayed with me since first encounter and it’s beautiful:

“How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.

What we do with this hour, or that one, is what we are doing.”

Please graar responsibly :)